Chronic UTI

In 2023, the NHS website in the United Kingdom added chronic UTI as a new category of UTI on their health information pages. You can read more about that here. We encourage you to share this important development with your doctor.

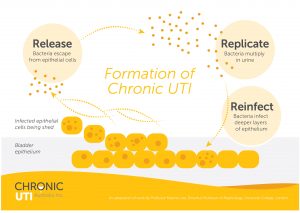

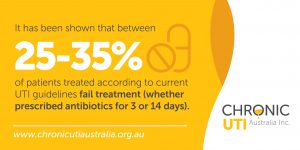

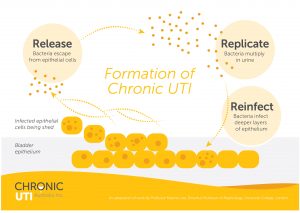

Chronic UTI can be the result of an improperly treated acute UTI. For example, chronic UTIs can occur when test-positive infections do not fully resolve after a standard course of antibiotics (which researchers say happens to between 25–35 percent of people1). Chronic UTIs can also be the result of being prescribed the wrong antibiotics or not receiving antibiotic treatment soon enough—or not at all. The following description is our simplified interpretation of complicated science.

Bacteria can invade cells in the bladder wall

An improperly treated UTI can lead to intracellular bacteria burrowing into the bladder and/or urethral lining (uroepithelium) where they safely hide away from further immune or antibiotic attack6 .

The bladder wall is usually around five to six cells deep and the bacteria have been shown to burrow down at each layer. Once inside, they hide in the spaces and fluid between cells (interstices and interstitial fluid) or they can invade the cells. This is referred to intracellular colonisation.

Leading research from the US3 and the UK4 has shown that bacteria, such as E. coli, have the ability to invade the cells lining the bladder wall very early on during an acute infection. There they can remain dormant for lengthy periods to avoid attack. Safely inside the bladder wall, the bacteria carry on with their mission to survive, divide and thrive, and will do so at various opportunities and intervals. For example, when the conditions are optimal, the bacteria take advantage and burst out of the cells and proliferate rapidly in the urine. This is usually described as an ‘acute’ UTI.

Bacteria can form biofilms

These clever bacteria have also evolved with the ability to form a biofilm—which is a natural, sticky coating that holds the bacteria closely together and protects them from harm. Bacterial biofilm can be multi-microbial (this means they can contain many different pathogens and species). They can form on the surface of the bladder wall as well as inside the bladder wall cells3, 4. Biofilm infections are a relatively new discovery and are estimated to be associated with around 80 percent of human bacterial infections2. Traditional UTI culturing methods are not designed to look for biofilm or intracellular infections, so it is unlikely that standard tests will detect this type of infection. (There is more on biofilms further down the page.)

The immune system fights back

Things become complicated when the cells of the bladder wall recognise the invasion and send signals (via cytokine signalling pathways) to launch an immune attack. As with all infections, this results in an inflammatory response as white blood cells answer the call to action. However, the white blood cells cannot find the invaders because they are cleverly hidden within the cells or covered by their protective biofilm shield. The white blood cells are not able to complete their mission and the whole immune response results in unpleasant symptoms from this on-going battle within the bladder. You can read more about how chronic UTI forms here.

Lower cell numbers do not meet diagnostic criteria

Unlike an acute infection that involves large numbers of rapidly thriving and dividing bacteria bubbling away furiously in the urine, a chronic infection involves much lower numbers of bacteria that have stuck firmly to the surface or are inside the cells. Subsequently, there will be lower numbers of white blood cells that usually do not meet the diagnostic thresholds applied for acute UTI. Low diagnostic numbers commonly associated with chronic UTI usually fly under the radar when it comes to microscopy, MSU cultures or urinary dipstick testing methods. You can read more about these thresholds on our UTI Testing page.

Symptoms continue as undetected bacterial infection continues to fester

The cells of the bladder wall shed naturally about every 100 days. When it is time for infected cells to shed, the bacteria sense their impending doom and jump into action. They vigorously multiply and break out of the dying cells so they can seek fresh, new uninfected cells to live in/on. This is described as a ‘planktonic flare’ which results in increased bacterial activity that overwhelms the body’s immune response, causing on onset of acute symptoms. Sometimes at this stage, white blood cells or bacterial numbers could achieve acceptable diagnostic thresholds and this is usually mistaken as a ‘new’ UTI. Low levels of white blood cells, epithelial cell shedding and planktonic bacteria from a chronic UTI are unlikely to satisfy these thresholds, which were only ever designed to diagnose acute pyelonephritis5 (a kidney infection)—a much more severe and serious form of infection. You can read much more about tests on our UTI Testing page.